Old German Account of Little Bighorn

Museums and archives often hold vast quantities of donated material that have never been fully examined or unpacked. Families frequently donate entire boxes of papers and objects from relatives, leaving institutions with far more unsorted collections than processed ones. As a result, historically significant items can sit unnoticed for years, waiting for the time, resources, and expertise needed to bring them to light.

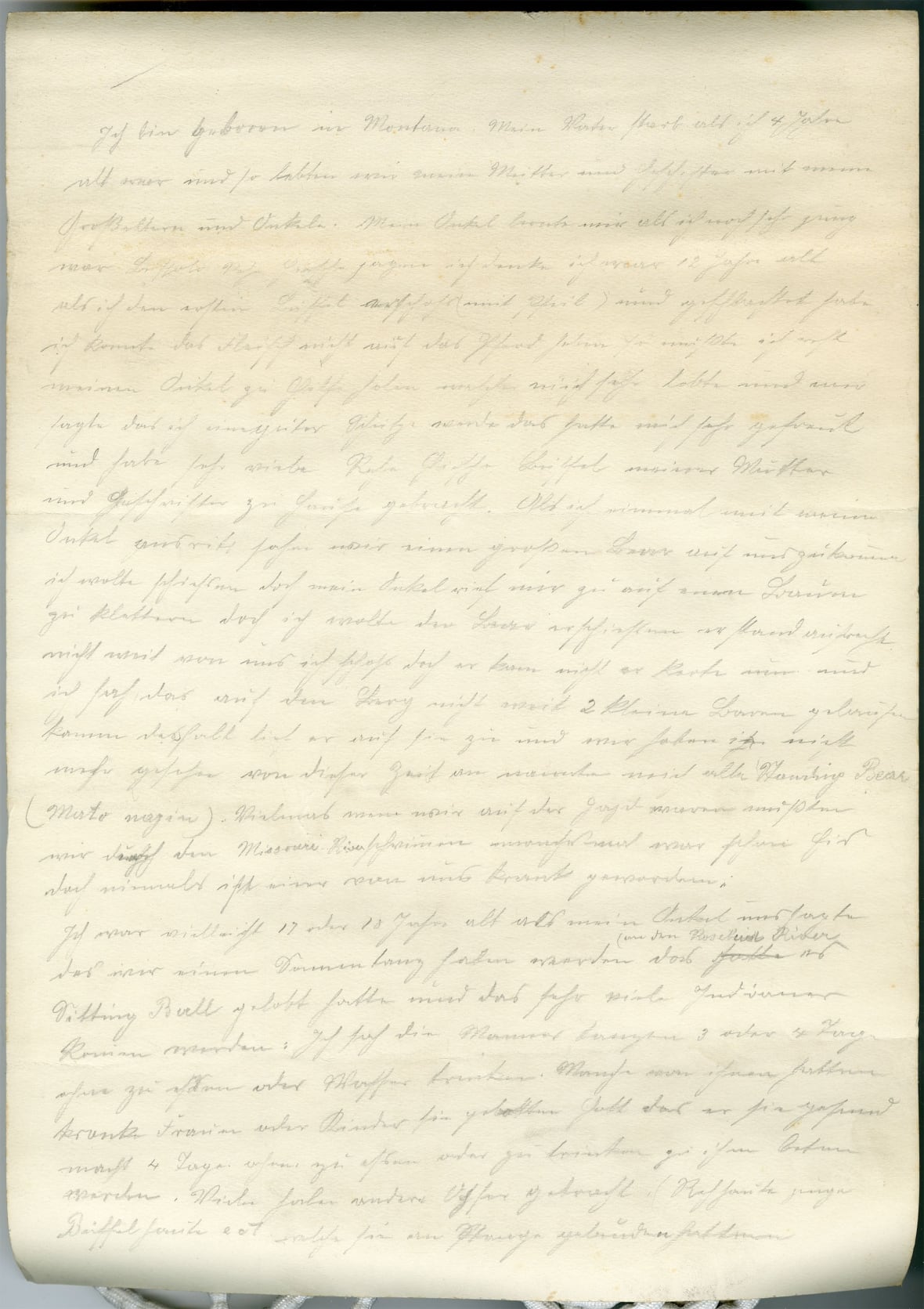

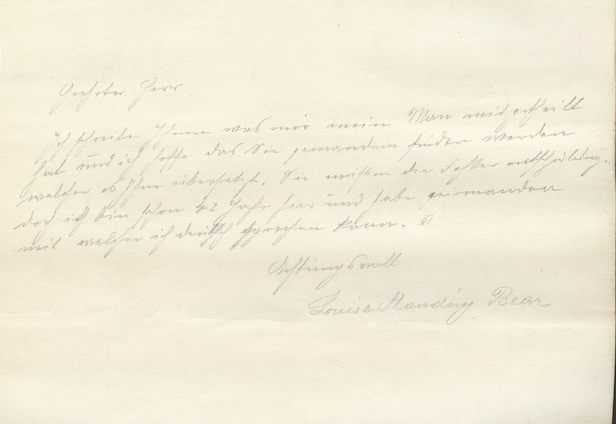

Samantha Thompson, an archivist at the Peel Art Gallery Museum and Archives in Brampton, Ontario, noticed such documents while sorting through donated archival boxes as part of her regular work. The documents stood out to her because of their unusual appearance and references to well-known historical names written in English : Custer, Rosebud River, Montana. The rest of the document was composed in an Old German script called Kurrent. This script was rarely used after the Second World War, and the text was not in a language anyone would have expected to find tucked away in a box of archival files in Ontario, Canada.

Kurrent was a centuries-old German handwriting system with roots in medieval scripts, widely used until the early 20th century. Its decline began in the 1910s, when it was replaced in German school systems by the simplified Sütterlin script, and this shift accelerated through the 1920s and 1930s as many writers moved to Latin-based handwriting. Kurrent disappeared almost entirely from official use after 1941, in part due to the Third Reich issuing a decree falsely claiming the script was of Jewish origin—a move intended to standardize writing across newly annexed territories where Kurrent was unfamiliar. Removed from schools and government correspondence, Kurrent survived only through independent study after the 1950s, becoming a Geheimschrift, or “secret script,” understood mainly by specialists.

It is important to note that Kurrent was not used exclusively for what is now understood as standard German. Modern divisions between languages—German, English, Dutch, and others—are often shaped by colonial, national, and administrative boundaries that present languages as fixed and separate, when in reality they exist on fluid spectrums of variation. Kurrent was used to write a range of Germanic languages and dialects, meaning that reading such a document involves more than deciphering an unfamiliar handwriting system; it also requires identifying which language or regional form is being used. In this case, while archivist Samantha Thompson was able to seek help from a colleague’s mother to read the script itself, further analysis was needed to parse the variety of nineteenth century Austrian German the text was written in.

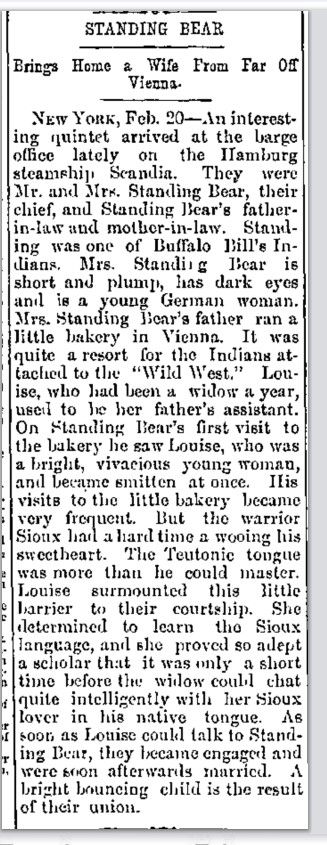

The author of the document was Louise Reineck Standing Bear, a Viennese nurse born in 1865. She met Mató Nájin , called Standing Bear in English, while he was touring Europe as part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, and the two later married before returning to the United States together. They went on to live at the Pine Ridge Reservation in the U.S. State of South Dakota for 42 years, and it was after those decades of shared life that Mató Nájin dictated a letter which Louise recorded for him.

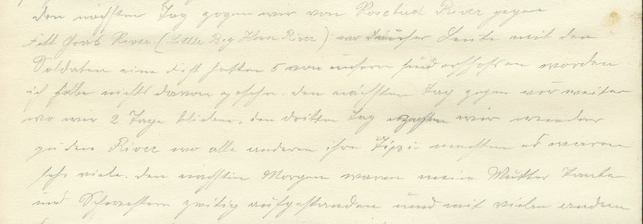

The letter describes the Battle of the Greasy Grass—known in English as the Battle of the Little Bighorn or Custer’s Last Stand—through the memories of Standing Bear, who was 17 years old at the time. He recalls attending a Sun Dance near the Rosebud River in the days before the battle, and he included a painting of the ceremony with the letter. He then recounts the moment Custer’s soldiers arrived, the alarm spreading through the camp, and his hurried ride toward the fighting alongside his uncle, capturing the sudden shift from ceremony to conflict as the battle began.

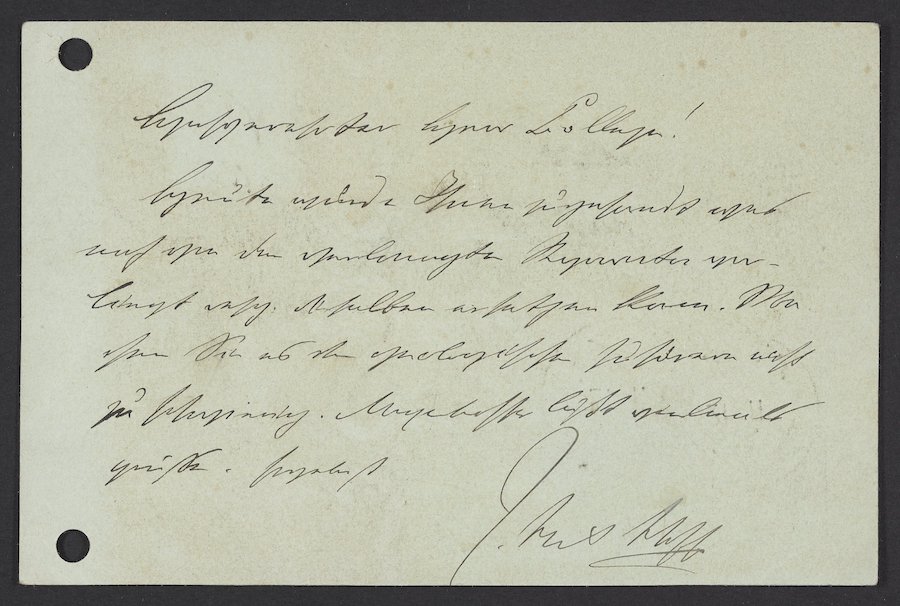

The story was dictated in Lakota, a fact made clear by a note Louise added at the bottom of the letter. In that note, she apologized for errors in her German, explaining that she had not spoken the language for many years. Although Louise Standing Bear understood spoken Lakota, she wrote the letter in Austrian German, reflecting the form of language and handwriting she had been taught in her education. Even though she had spoken German not for 42 years – more than half her life- she still wrote in German because it was the most efficient and effective way to compose these ideas, despite the fact that they had been communicated to her in a completely different language family.

Modern readers can understand this disconnect because there is clear evidence of it in writing practices today. Habits such as placing two spaces after a period point to older typing systems that persist long after they are no longer standard. Other examples include using all caps for emphasis, maintaining cursive signatures despite cursive no longer being widely taught, or following rigid letter formats inherited from the typewriter era. These practices endure because writing is a learned system that people tend to carry with them for life.

Multilingual speakers are differently adept across their multiple languages. As writing is an acquired skill, not an innate one, people are often significantly better at writing in the language(s) in which they’ve had the most practice. In the 1800s and well into the 1900s many people learned to write in schools but then did not write very much in their personal lives. Thus there are generations of people who, when they were called on to write later in their lives, would produce writing in the style that they were taught in.

https://www.archives.gov/citizen-archivist

Today, many museums are actively working with volunteers and specialists to transcribe and translate historical cursive writing, recognizing that writing is a learned, structural habit that tends to persist for a lifetime. One well-known example is the National Archives Citizen Archivist Program, which invites the public to help transcribe, tag, and translate historical documents that staff alone do not have the capacity to process. Programs like this highlight how much archival material remains unread—not because it lacks value, but because of the time-lag between the writing styles people learned earlier in life and the styles later generations know how to read. As a result, countless documents written in unfamiliar older forms remain overlooked, and there is much documented history yet to “discover”.